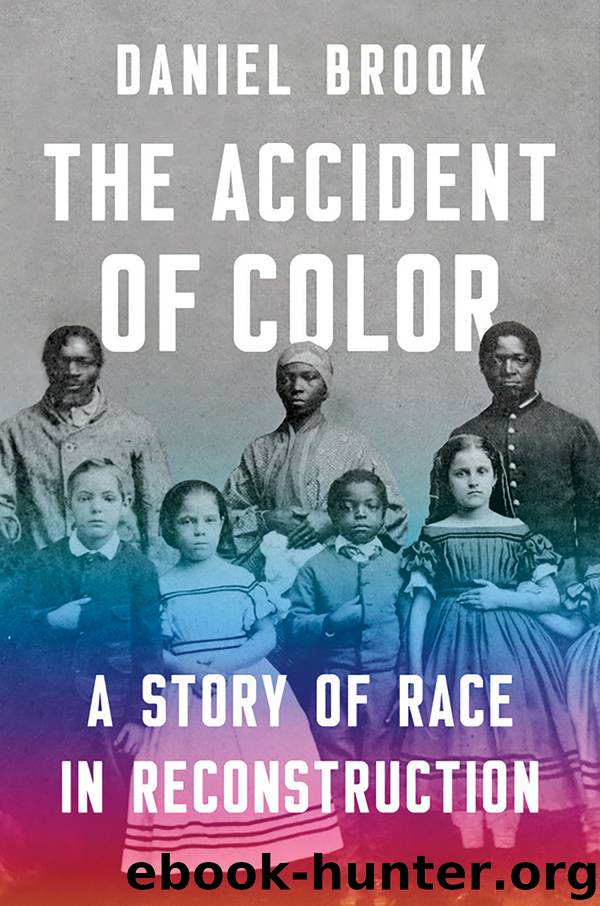

The Accident of Color by Daniel Brook

Author:Daniel Brook

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2019-04-11T16:00:00+00:00

As Sumner’s bill languished in Washington, D.C., the civil rights laws on the books in the Southern states needed to be enforced. Activists realized early on that no matter what the lawbooks said, only integrated police forces could ensure they were carried out. In New Orleans and Charleston, the police departments were integrated quickly and thoroughly, while many other jurisdictions lagged behind. Even when Tennessee still had its law on the books prohibiting segregation on railroad cars, there wasn’t a single African-American policeman in Nashville or Memphis to enforce it.

The creation of New Orleans’s Metropolitan Police was a tribute to activist pressure. The week after the city’s streetcars were desegregated, New Orleans Tribune publisher Louis Charles Roudanez wrote an open letter all but issuing an order to Mayor Heath: “Let him appoint colored police officers.” The paper’s editors made the tendentious argument that African-American police officers were required in New Orleans because, by the one-drop rule (if not by the official census figures), New Orleans was a majority-African-American city. Despite the vociferous protests of inhabitants proclaiming their pristine whiteness, “everybody knows that one-half at least of the inhabitants of the Crescent City have more or less of African blood in their veins,” the newspaper reminded a populace in denial.

Reconstruction’s supporters were sympathetic to integrating police forces out of simple pragmatism. After all, the murderous rampages that had brought on Radical Reconstruction had been led by all-white police forces in Memphis and New Orleans. On May 28, 1867, the Louisiana governor announced the appointment of what he dubbed a “newly enfranchised” citizen, Charles J. Courcelle, to the state’s Board of Police Commissioners. That June, over a dozen African-Americans joined the force. And in 1868, the state legislature created the state-run Metropolitan Police to patrol the city and its neighboring parishes. Three of the five commissioners appointed to run the Metropolitan Police were men of color and the rank and file was majority African-American. In the wake of white complaints, the percentage dropped to just over a quarter, roughly in line with percentage of the city that self-identified as African-American (albeit a far cry from the Tribune’s one-drop-rule population count). Among the white officers, most were international immigrants, largely from Ireland and Germany. Of the American-born whites, two-thirds were native-born Southerners and one-third Yankees. Creoles of color were spectacularly overrepresented among the police; fully 80 percent of the African-American officers came from the biracial Francophone community.

In Charleston, the police force was integrated in 1868 with the appointment of Richard Holloway, a member of one of the city’s leading Brown families. African-Americans, most of them antebellum freemen, flocked to join the ranks and by 1870 over 40 percent of the Charleston police were men of color. When Scribner’s correspondent Edward King visited Charleston in 1873, he informed his readers that “the present police force of the city is about equally divided into black and white [and] at the Guard-House one may note white and black policemen on terms of amity.” It was a

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12098)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5370)

Navigation and Map Reading by K Andrew(5156)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4390)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(4150)

5 Steps to a 5 AP U.S. History, 2010-2011 Edition (5 Steps to a 5 on the Advanced Placement Examinations Series) by Armstrong Stephen(3733)

Three Women by Lisa Taddeo(3433)

Water by Ian Miller(3185)

The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels, and the History of American Comedy by Nesteroff Kliph(3079)

Drugs Unlimited by Mike Power(2594)

A Short History of Drunkenness by Forsyth Mark(2297)

DarkMarket by Misha Glenny(2212)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2209)

The House of Government by Slezkine Yuri(2206)

The Library Book by Susan Orlean(2069)

Revived (Cat Patrick) by Cat Patrick(1991)

The Woman Who Smashed Codes by Jason Fagone(1973)

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie(1913)

Birth by Tina Cassidy(1904)